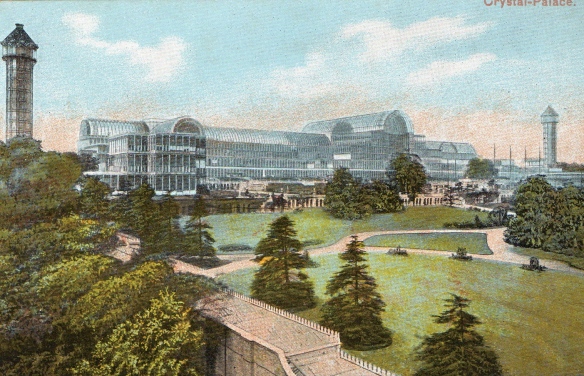

One of my favourite pieces of the puzzle that is London history is the Crystal Palace, so it’s high time Crystal Palace Park – its last resting place – made an appearance in this blog. Designed by Joseph Paxton (immortalised in the stone bust pictured below), and made from plate glass and cast iron, this huge greenhouse-like structure was the former home of the the 1851 Great Exhibition, held in Hyde Park, and later moved south to Sydenham.

This move followed a heated debate about the future of the Palace at the end of the temporary exhibition. At this point it was re-designed and rebuilt on a much larger (and I personally think more attractive) scale – the move and rebuilding costing a massive £1,300,000. This new version opened in 1854 and was to host numerous concerts, fireworks displays, exhibitions, and feature a Natural History Collection and a number of ‘Fine Art Courts’, where visitors could walk amongst replicas of architecture, sculpture and decorative arts from various eras and cultures.

The 1911 Festival of Empire was held in the park, and saw the construction of three-quarter size replicas of all of the Commonwealth countries’ parliament buildings, as well as an Australian vineyard, an Indian tea plantation and a south African diamond mine. A miniature railway was built to transport visitors between the various sites.

Tragically, despite the efforts of 89 fire engines and 381 firefighters, the Palace was lost in a massive fire on the night of 30th November, 1936. The two giant water towers – designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel to cater for the massive amount of water required for the Palace’s extensive water features – were the only Palace buildings left standing. These were later demolished during the Second World War as it was thought that German aircraft might use them as landmarks. The base of one can still be seen just outside the Crystal Palace Museum.

And there are plenty of other remains still scattered around the park: many of the terraces, a number of the sphinxes, several of the statues, including the particularly striking headless one above, to name but a few. These now languish in a rather splendid state of decay and are my favourite feature of the park.

And there are plenty of other remains still scattered around the park: many of the terraces, a number of the sphinxes, several of the statues, including the particularly striking headless one above, to name but a few. These now languish in a rather splendid state of decay and are my favourite feature of the park.

A hugely popular feature of the park today is the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs – life-sized models designed by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, arrayed around a lake in the south-east corner of the park. These constitute the first ever sculptures of dinosaurs, unveiled in 1854 as part of the renovation of the park. In fact, they are not actually all dinosaurs – some are extinct animals. In true Victorian style, Hawkins threw a dinner for 21 guests inside one of the models on New Year’s Eve in 1853. At one point the models were so neglected they were covered with foliage, but were restored in 1952 and again in 2002.

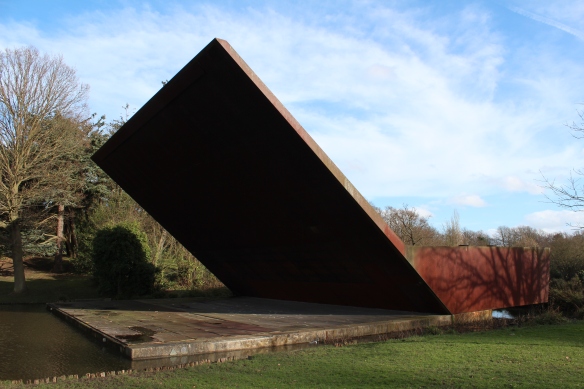

The park is also home to London’s largest maze, first built in 1879 and then re-created in 1987 and refurbished in 2009. There are of course other newer features of interest within the park, not least of which is the ultra-modern Concert Platform, designed in 1997 by Ian Ritchie Architects:

The Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, in the middle of the park, is probably not generally considered to be the its most appealing attraction, but I feel it has a certain brutal, modern appeal:

If you’d like to learn more about the Crystal Palace, drop by the Crystal Palace Museum in the south-west corner of the park. Housed in the former Crystal Palace Company’s School of Practical Engineering, this museum may contain only one room but the information within it is comprehensive: if you visit here knowing nothing about the Crystal Palace you will leave knowing just about everything you should! It’s open Saturdays and Sundays, 11-4 summertime and 11-3:30 in winter.

The Crystal Palace is back in the news again of late due to plans by a Chinese company to rebuild it (in its massive, original size) in the park. I don’t feel well equipped enough to comment too much on this highly controversial project (please feel free to leave your own thoughts below) but it would be a huge loss if the remaining statuary was not preserved and if too much of the park was lost to public access. On the upside, the plan would reinstate Paxton’s Grand Central Walk, a promenade that once ran along the centre of the park and was later obstructed by the sport centre. A petition raising concerns about the development can be found here. In the meantime, these photographs capture the park as it is now – and may not be forever…